Imposing invariants in Scala

Imagine a opera house allows reservations to a show. For each reservation two people can come: the buyer of the reservation himself and his guest.

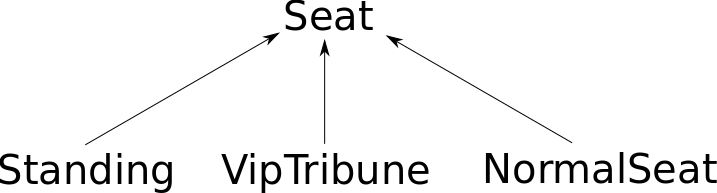

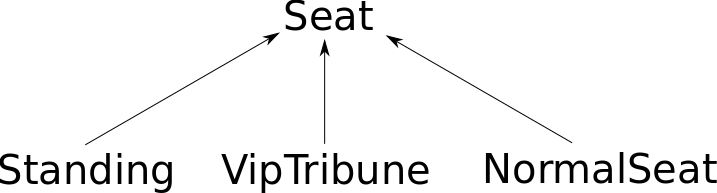

As in any show-house, there are many types of seats; some are standing, some normal and some on VIP tribunes.

As a restriction from the opera house, both buyer and guest must be on the same seating area. For example, it is not permitted for one ticket to be standing while the other for the normal seated area.

I believe this is what people call an invariant. A requirement that must hold for the data to have meaning.

How to enforce then this constraint?

Let us first define the data types relevant to the problem:

sealed trait Seat

case class NormalSeat(row: Int, column: Int) extends Seat

case class VipTribune(tribuneId: String) extends Seat

case object Standing extends Seat

The following diagram is useful for discerning the relation above and understanding the explanations that follow.

We also have:

case class Ticket[SeatType <: Seat](

verificationCode: String,

price: Int,

seat: SeatType

)

case class Reservation[SeatType <: Seat](

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

)

The first thing to notice is that the above does not deliver what we want. The following compiles:

val reservation = Reservation(

usertTicket = Ticket("id1", 123, VipTribune("east")),

guestTicket = Ticket("id2", 123, Standing)

)

The compiler tries to infer the type SeatTypefor reservation. From user ticket on line 2, it thinks it is VipTribune. The compiler is satisfied since this is a sub-type of Seat which is an upper type bound on Reservation. This is contradicted on the 3rd line, as we encounter type Standing for the guest ticket. Bad news since type SeatType on line 2 and SeatType on line 3 refer, well, to the same type!

Before launching an error, the compiler realizes both Standing and VipTribune are actually sub-types of Seat; this means they can pretend to be their super-type (Seat). Because Seat respects the type bound Seat <: Seat, the compilation is successful with val reservation: Reservation[Seat].

There are at least 4 ways to enforce the restriction of the opera-house:

- Using require(condition) on the class constructor of Reservation

- Hiding the public constructor of the class, defining a public one that validates and returns Option[Reservation]

- Using generalized type constrains

- Using OOP - subtyping

1. Using require(condition) on the class constructor of Reservation

case class Reservation[SeatType <: Seat](

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

){

private def verifyTypeRestriction: Boolean = (userTicket.seat, guestTicket.seat) match {

case (NormalSeat(_, _), NormalSeat(_, _)) => true

case (VipTribune(_), VipTribune(_)) => true

case (_: Standing.type , _: Standing.type ) => true

case _ => false

}

require(verifyTypeRestriction)

}

On this approach we delegate to the users of case class Reservation the responsibility of never trying to instantiate a value that does not conform to the rules. If they do breach the rule, the code compiles but throws an exception at run time.

While this is the least adequate of the solutions, we can have the peace of mind that, if it does blow up, it will do so on instantiation of the object. Meaning that some other block of code further down can expect the invariant to be respected and avoid dealing with the inconsistent cases (since if the block of code is being executed, the previous instantiation succeed). We have centralized the point of failure to the instantiation of the object.

Notice lastly that extending Reservation does not bypass the constructor, so that the require(condition) will always be executed.

2. Hiding the public constructor of the class, defining a public one that validates and returns Option[Reservation]

The idea here is to make it impossible for future users of Reservation to create an instance directly but only through one single method, engineered by us to take into account unlawful constructor parameters. The method ought to return a Reservation boxed in a data type that allows to represent something went wrong like the Option/Try/Either.

It is then the responsibility of the user to deal with the returned boxed type accordingly.

There are two ways to achieve this. The sub chapter 19.2 in [1] is useful in what follows.

The first is by adding private before the parameter list of the class, and then defining an apply method on the companion object.

class Reservation[SeatType <: Seat] private (

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

)

While one does not need to name the method apply, it must be on the companion object; otherwise one does not have access to the constructor which is defined as private. Recall that the companion object has the same access rights as the class.

object Reservation {

def apply[SeatType <:Seat]( userTicket: Ticket[SeatType], guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]): Option[Reservation[SeatType]] = (userTicket.seat, guestTicket.seat) match {

case (NormalSeat(_, _), NormalSeat(_, _)) => Some(new Reservation(userTicket, guestTicket))

case (VipTribune(_), VipTribune(_)) => Some(new Reservation(userTicket, guestTicket))

case (_: Standing.type , _: Standing.type ) => Some(new Reservation(userTicket, guestTicket))

case _ => None

}

}

Notice that trying to extend Reservation on another file, possibly bypassing our apply method, will not work.

As an alternative, one can hide the case class altogether, i.e. not only the constructor but also the name (so that we cannot use it as a type). To that end one defines a trait which exposes the implementation that we want.

sealed trait Reservation[SeatType <: Seat] {

val userTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

val guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

}

And on the companion object we have the actual implementation:

object Reservation {

private case class ReservationImpl[SeatType <: Seat](

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

) extends Reservation[SeatType]

def apply[SeatType <: Seat](userTicket: Ticket[SeatType], guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]): Option[Reservation[SeatType]] = (userTicket.seat, guestTicket.seat) match {

case (NormalSeat(_, _), NormalSeat(_, _)) => Some(ReservationImpl(userTicket, guestTicket))

case (VipTribune(_), VipTribune(_)) => Some(ReservationImpl(userTicket, guestTicket))

case (_: Standing.type , _: Standing.type ) => Some(ReservationImpl(userTicket, guestTicket))

case _ => None

}

}

Notice the relevance of declaring the trait sealed. It prevents the user from extending the trait by another class on some other file, which would allow him to bypass the factory method apply above. Equally important is to have ReservationImpl as private so that it cannot be extended on client code. In fact, I guess we could even ignore ReservationImpl altogether and instantiate an anonymous class instead.

This approach has a disadvantage concerning type erasure which also plagues the next approach using generalized type constraints. We will address the issue there.

3. Using generalized type constrains

This is the most novel of the approaches and, as far as I know, could not be achieved on Java, contrary to the remaining solutions.

Let us recall the original problem. On

case class Reservation[SeatType <: Seat](

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

)

the compiler can impose SeatType to have as upper bound the type Seat. It cannot however impose SeatType to be one of the sub-types exclusively. Meaning that upon userTicket: Ticket[VipTribune] and guestTicket: Ticket[NormalSeat], both VipTribune and NormalSeat can pretend to be type Seat which would result in userTicket: Ticket[Seat] and guestTicket: Ticket[Seat] which in turn conforms with the upper bound constraint (Reservation[SeatType <: Seat]). The issue really is that a given type A is a subtype of itself.

The trick on this approach is to use a generalized type constraint. These are not built-in features of the language (like type bounds) but rather smart ways some smart people have engineered to leverage the type system of Scala to accomplish some more impressive things.

There are 2 or 3 generalized type constraints on the standard library of Scala on package scala.Predef which is imported by default. One of the most famous is <:<.

The one we are going to use is found on the external library Shapeless by Miles Sabin.

It is written =:!=[A, B]; this is a parameterized trait named =:!= with two types. This can also be written A =:!= B.

I will not try to explain the intricacies of these things. A detailed explanation on related type constraints can be found here. I hope to transmit a feeling on how to use them.

Each of these type constraints is used with a specific goal. The goal of A =:!= B is to impose that types A and B are different, whatever they might be. This is accomplished via implicits. Specifically, you declare an implicit variable of type A =:!= B, where A and B are some two types you want to make sure are different. I would say that normally, either A, B or both are abstract/parameterized types, like type Ole below.

import shapeless.=:!=

def foo[Ole](a: Ole)(implicit ev: =:!=[Ole, Int]): A = a

foo[String]("E.Near rocks.") /* Compiles */

foo[Int](5) /* Does not compile */

foo[Boolean](true) /* Compiles */

Briefly, if Ole and Int are different, the compiler will be able to (always) find the required implicit and succeed the compilation. If they are the same, something else happens and a compilation error is raised. How exactly using the syntax (implicit ev: =:!=[Ole, Int]) achieves that behavior is beyond this post; it should be accepted as the truth.

This can however be used to tackle our problem:

import shapeless.=:!=

case class Reservation[SeatType <: Seat](

userTicket: Ticket[SeatType],

guestTicket: Ticket[SeatType]

)(implicit ev: SeatType =:!= Seat)

The implicit evidence ev will demand the compiler to find proof that SeatType, whatever type it might be, must not be type Seat. If it cannot, it throws a compilation error. With figure 1 as guidance, because abstract type SeatType has as upper bound the concrete type Seat, and since given the generalized type constraint, SeatType must not be Seat, then it must surely be one of Standing, VipTribune or NormalSeat. Problem solved. So, in contrast with the other 2 solutions so far seen, an attempt to instantiate a reservation with unsound parameters is caught during compilation:

val standing = Standing

val normalSeated = NormalSeat(4, 5)

val tribuneSeat = VipTribune("east")

// Compiles

val bar = Reservation(

Ticket("id1", 123, normalSeated),

Ticket("id2", 456, normalSeated)

)

// Will never compile

val foo = Reservation(

Ticket("id1", 123, standing),

Ticket("id2", 456, tribuneSeat)

)

// Will never compile

val baz = Reservation(

Ticket("id1", 123, normalSeated),

Ticket("id2", 456, tribuneSeat)

)

When it does not compile we get the error:

ambiguous implicit values:

[error] both method neqAmbig1 in package shapeless of type [A]=> A =:!= A

[error] and method neqAmbig2 in package shapeless of type [A]=> A =:!= A

[error] match expected type com.github.cmhteixeira.invariants.Seat =:!= com.github.cmhteixeira.invariants.Seat

[error] val foo = Reservation(

[error] ^

The error message is not very helpful, but one must live with it ¹

This approach, similarly to the 2 other approaches, suffers from an inconvenience. The type SeatType on a given reservation is lost at run time due to type erasure. We cannot pattern match on a given reservation as on the following example:

def guideUsersToTheirSeat(reservation: Reservation[Seat]): String = reservation match {

case _: Reservation[Standing.type] => "Go to gate 1. You and your guest must stand."

case reser: Reservation[VipTribune] => s"Go to gate 2. Your tribune is named ${reser.guestTicket.seat.tribuneId}"

case reser: Reservation[NormalSeat] => s"Go to gate 3. You and your guest are in a seats ${reser.userTicket.seat.column} and ${reser.guestTicket.seat.column} respectively"

}

The method guideUsersToTheirSeat is useless as it will always follow the first case on the match.

The compiler will in fact warn us of this :

non-variable type argument com.github.cmhteixeira.invariants.Standing.type in type pattern com.github.cmhteixeira.invariants.Reservation[com.github.cmhteixeira.invariants.Standing.type] is unchecked since it is eliminated by erasure

[warn] case a: Reservation[Standing.type] => "Go to gate 1"

Fortunately the type parameter SeatType on Reservation is not a phantom type. It is associated with the value of seat within each Ticket (userTicket and guestTicket) of the reservation. To avoid the above problem we must therefore pattern match on the seats of each ticket.

def guideUsersToSeat(reservation: Reservation[Seat]): String = {

val userSeat: Seat = reservation.userTicket.seat

val guestSeat: Seat = reservation.guestTicket.seat

(userSeat, guestSeat) match {

case (_: Standing.type, _: Standing.type ) => "Go to gate 1"

case (userSeat: VipTribune, _: VipTribune ) => s"Go to gate 2. Your tribune is named ${userSeat.tribuneId}"

case (userSeat: NormalSeat, guestSeat: NormalSeat ) => s"Go to gate 3. You and your guest are in a seats ${userSeat.column} and ${guestSeat.column} respectively"

}

}

The code above will work well and do what we are looking for. But we are not quite there yet. The compiler still finds a warning:

match may not be exhaustive.

[warn] It would fail on the following inputs: (NormalSeat(_, _), Standing), (NormalSeat(_, _), VipTribune(_)), (Standing, NormalSeat(_, _)), (Standing, VipTribune(_)), (VipTribune(_), NormalSeat(_, _)), (VipTribune(_), Standing)

[warn] (userSeat, guestTicket) match {

[warn] ^

The compiler is concerned we might not be considering all possible combinations of seats within a reservation.

We are not considering for the cross cases (e.g. (Standing, NormalSeat)) because with the above tricks, we are certain that any created instance of Reservation will always respect the invariant.

The compiler isn’t. For it, a single Reservation[Seat] might contain tickets in different seating areas. We have to match on both tickets (user and guest) each of which, as far as the compiler goes, can be of any type (Standing, VipTribune, NormalSeated, Seat).

Because we (arguably) know more than the compiler in this case, we can tell him not to be concerned with the non-exhaustive pattern match with an annotation (chapter 15.5 at [1]):

((userSeat, guestTicket): @unchecked) match {

Which will prevent the warning during compilation.

4. Using OOP - Subtyping

This is the approach most of us would follow. Probably the most pragmatic.

It requires having a bare trait Reservation and extending it for every sub-type of Seat. When there are many sub-types, this would become very repetitive.

sealed trait Reservation[+SeatType <: Seat]

case class ReservationSeated(

userTicket: Ticket[NormalSeat],

guestTicket: Ticket[NormalSeat]

) extends Reservation[NormalSeat]

case class ReservationStanding(

userTicket: Ticket[Standing.type],

guestTicket: Ticket[Standing.type]

) extends Reservation[Standing.type]

case class ReservationVipTribune(

userTicket: Ticket[VipTribune],

guestTicket: Ticket[VipTribune]

) extends Reservation[VipTribune]

On the other hand, all the type information is carried on at run-time. We can for example pattern match with confidence:

def guideUsersToSeat(reservation: Reservation[Seat]): String = reservation match {

case ReservationStanding(_, _) => "Go to gate 1."

case ReservationSeated(userTicket, guestTicket) => s"Go to gate 2. You and your guest are in a seats ${userTicket.seat.column} and ${guestTicket.seat.column} respectively "

case ReservationVipTribune(userTicket, _) => s"Go to gate 3. You are on tribune ${userTicket.seat.tribuneId}"

}

And because none of our sub-typed Reservation classes has tickets with seats of different types, the invariant is always assured.

This post is also on the author’s blog at https://aerodatablog.wordpress.com/

Do you know any other approach? I would be happy to hear it. Just write on the comment section.

Footnotes

- There is an answer on StackOverflow by some Régis Jean-Gilles that attempts to solve that problem. Did not bother to analyse it. Curious also why Shapeless does not have it (assuming that it works) -https://stackoverflow.com/questions/6909053/enforce-type-difference